His Three Daughters (15, 104 mins)

Verdict: Beautifully observed

Death, it occurred to me while watching the new Netflix release His Three Daughters, has been more of a constant in cinematic story-telling than anything else, including love.

From the earliest motion pictures, death has loomed large on the silver screen, although normally, for manifest dramatic reasons, of the sudden violent kind.

Understandably, the sort of death with which most of us become familiar at least a few times in our lives, the drawn-out passing of a parent or friend, is dramatised far less often.

But when it is done well, it can be more moving, more thought-provoking, than almost anything.

That’s why the new Pedro Almodovar film, The Room Next Door, won the main prize at the Venice Film Festival earlier this month. It’s a compelling study, superbly acted by Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore, of the ethics and manners surrounding the right of a terminally ill person to choose how and when to die.

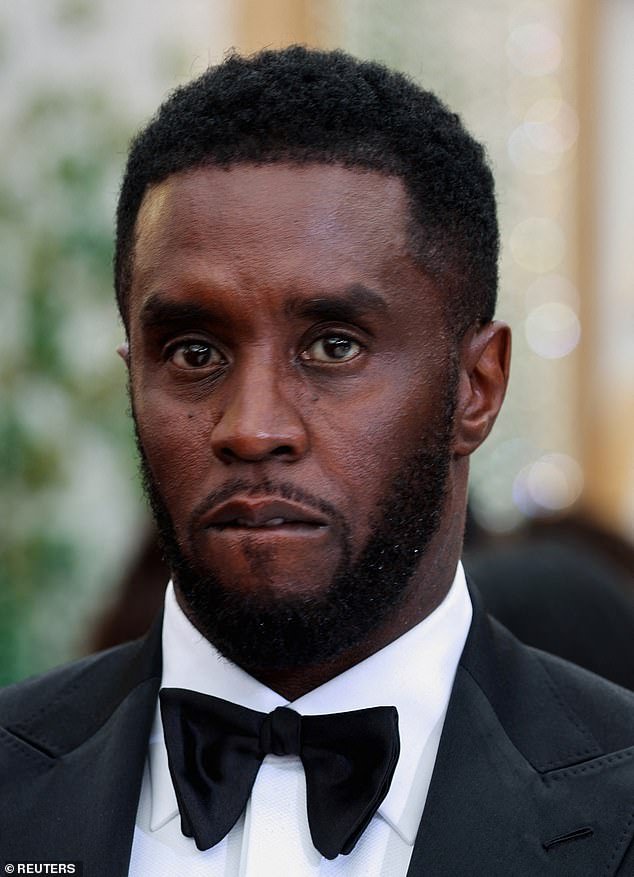

Natasha Lyone as Rachel, Elizabeth Olsen as Christina (centre) and Carrie Koon as Katie in His Three Daughters

Carrie Koon plays Katie – the oldest daughter who is bossy, brittle and highly strung

His Three Daughters offers a different but no-less-absorbing take on the subject of death. A man, of whom we see very little, is receiving end-of-life care in his New York City apartment.

The wellspring of the dramais the relationship between the trio of women who are waiting for him to expire: his daughters Katie (Carrie Coon), Christina (Elizabeth Olsen) and Rachel (Natasha Lyonne).

Katie, the eldest, is bossy, brittle, highly strung. On the evidence of her phone calls home, she is just as uptight as a mother. Nor, though she lives elsewhere in New York, was she an especially attentive daughter. But now, with her father on his deathbed, she is trying to take charge, agonising over his obituary and a do-not-resuscitate form that needs signing, yet exuding precious little warmth or compassion.

The middle daughter, Christina, has flown in from afar so at least has an excuse for seeing little of the old man. She has a young child and a life that to the outside eye seems nigh-on perfect, although of course such lives never are, either in the movies or anywhere else.

The youngest, Rachel, is addicted to pot and her throaty voice is either that of a chain-smoker or she’s preparing for a Marge Simpson sound-alike contest. Katie, with whom she clashes repeatedly, thinks she is hopelessly irresponsible. But gradually we realise that she is the only one properly grieving the impending death of their father, and indeed the one who devotedly cared for him, shared his apartment and will inherit it when he’s gone.

Within this sibling dynamic there are lots more nuances, and a couple of twists I won’t share. Not that it would spoil anything if I did, because the dialogue and performances need to be savoured. His Three Daughters is exquisitely acted (especially by Olsen, who somehow turns the least interesting role into the most watchable) and cleverly, wittily scripted by writer-director Azazel Jacobs (whose 2017 film The Lovers was another gem about the shifting sands within family relationships).

Elizabeth Olsen plays middle daughter Christina who has flown in from afar and therefore has an excuse for not visiting her ill father

The youngest daughter Rachel, played by Natasha Lyonee, is a chain-smoker but is the only child that devotedly cared for their father. She is set to inherit the apartment when he dies

Whether Jacobs wove this story out of personal experience or just his keen observation of other people, I don’t know. Either way, he writes beautifully for women. I watched it with my wife who laughed aloud at an exchange between Rachel and Christina, who, the former suggests, will probably go on and ‘pop out’ more kids.

Christina bridles at this description of childbirth. ‘Nothing pops,’ she says, indignantly. ‘There’s no popping.’

His Three Daughters is on Netflix.

The Substance (18, 140 mins)

Verdict: Grisly horror-satire

There’s plenty of popping in The Substance. Popping, in fact, might be the least of it, alongside snapping, bursting, oozing and squelching, in a grotesque body-horror satire that isn’t for the squeamish but might be for the ticklish, if you can find the funny side.

Demi Moore gives a bold, career-best performance as Elisabeth Sparkle, a once-mighty Hollywood star reduced to presenting a workout show on TV, and then stripped even of that by her odious boss (Dennis Quaid), who is looking for someone younger.

So she does what anyone might in the same circumstances; she signs up fora top-secret drug — the titular ‘substance’ — which promisesto reproduce her in younger form in seven-day cycles. And it works. She gets a precious week as her youthful self (played by Margaret Qualley) before again becoming the unwanted 50-something version.

Writer-director Coralie Fargeat has oodles of bloody and gooey fun with this, especially the scene in which, on her bathroom floor, Sparkle mark I spawns Sparkle mark II, who is known as Sue, and duly becomes a huge TV star.

Demi Moore gives a bold, career-best performance as Elisabeth Sparkle, a once-mighty Hollywood star reduced to presenting a workout show on TV

Dennis Quaid plays Harvey in The Substance which is playing in cinemas now

Yet for all its dystopian grisliness, Oscar Wilde would have recognised this story, which echoes The Picture Of Dorian Gray, but of course has particular resonance in today’s looks-obsessed society.

As for Moore, it’s always especially poignant in the movies to watch (with respect) a has-been play a has-been. She does it wonderfully.

The Substance is in cinemas now.

All rise for an enthralling French court case

The Goldman Case (12A, 115 mins)

The winner of the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival last year was Anatomy Of A Fall, a brilliant, mostly French-language whodunnit, in which the details of a dysfunctional marriage were aired, rivetingly, in a courtroom.

Well, I wouldn’t compare French court-of-law dramas with London buses, because it’s not as though we knew we were waiting for them, but here’s another one, and very good it is, too.

The Goldman Case tells a true story, that of Pierre Goldman (Arieh Worthalter), a Jewish, left-wing firebrand who was convicted of committing several armed robberies.

Two women died during one of the robberies and in 1974 he was sentenced to life imprisonment. But there was doubt about the integrity of the conviction and the taint of anti-Semitism.

Two years later, with Goldman volubly supported by the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and the actress Simone Signoret, among others, there was a highly publicised second trial.

The Goldman Case tells the true story of Pierre Goldman, played by Arieh Worthalter (Pictured)

Unlike Anatomy Of A Fall, Cedric Kahn’s film takes place almost entirely in court, and consists to a very large extent of French people yelling at each other.

But it is shot in a grainy documentary-style and is all the better for it, as it builds to a climax that is genuinely enthralling.

The Goldman Case is in cinemas now.